Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) may be the great idealiser of American smalltown life, but many of his paintings took their cues from Dickens, and they thus have an English tang. None more so than Merrie Christmas (pictured below), which Rockwell painted for the cover of 7 December 1929 edition of the Saturday Evening Post: Tony Weller, the philosophising coachman father of Mr Pickwick’s manservant Sam, is shown cracking his whip with one hand and doffing his holly-spiked hat with the other.

Resplendent in a great blue coat, a red scarf and beige breeches and waistcoat, as fat-bellied if not as jowly as the Weller Sr drawn by Phiz, Rockwell’s Tony is seasonably jolly - yet his glowing red cheeks and nose indicate that he is also seasonably tipsy, and that his passengers can expect a wayward ride home. Without the suggestion of bibulousness, the picture would have been as unctuous as that of the smiling coal miner in Mine America’s Coal (1944), which Rockwell painted for a patriotic propaganda poster, but Tony’s boozy pallor makes it wonderfully sly.

Resplendent in a great blue coat, a red scarf and beige breeches and waistcoat, as fat-bellied if not as jowly as the Weller Sr drawn by Phiz, Rockwell’s Tony is seasonably jolly - yet his glowing red cheeks and nose indicate that he is also seasonably tipsy, and that his passengers can expect a wayward ride home. Without the suggestion of bibulousness, the picture would have been as unctuous as that of the smiling coal miner in Mine America’s Coal (1944), which Rockwell painted for a patriotic propaganda poster, but Tony’s boozy pallor makes it wonderfully sly. American Chronicles contains 43 canvases and, clustered on one wall at the Fort Lauderdale museum, all 323 of Rockwell’s Post covers, which he painted between 1916 and 1963. The first part of the exhibition focuses on Rockwell’s anecdotal paintings, depicting the quotidian, commonplace experiences of ordinary people and ranging from the whimsical to the serious. I found some of these canvases incredibly moving, among them Girl at Mirror, a 1954 Post cover (pictured above), possibly influenced by Picasso’s painting of the same name and Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s The Artist’s Daughter. It shows a girl of about 12, dressed in an old cotton slip and contemplating her face in front of a mirror, which has been propped against a chair, with her clenched hands raised to her chin. Her braids are tightly bound at the back of her head and she is wondering how she would look if her hair were styled like that of Jane Russell, who stares grimly back from a portrait in the magazine on the girl’s lap. On the floor beside the mirror is a discarded doll; at the girl’s foot is a hairbrush, comb, a lipstick and a tin of rouge, both open. The girl is poised between childhood and womanhood and her innocence hovers in the balance. But though she’ll be prey for the cosmetics industry in a year or two, her wistfulness suggests she already has a sense of proportion about her looks. She won’t be a movie star, but she’ll pass muster.

American Chronicles contains 43 canvases and, clustered on one wall at the Fort Lauderdale museum, all 323 of Rockwell’s Post covers, which he painted between 1916 and 1963. The first part of the exhibition focuses on Rockwell’s anecdotal paintings, depicting the quotidian, commonplace experiences of ordinary people and ranging from the whimsical to the serious. I found some of these canvases incredibly moving, among them Girl at Mirror, a 1954 Post cover (pictured above), possibly influenced by Picasso’s painting of the same name and Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s The Artist’s Daughter. It shows a girl of about 12, dressed in an old cotton slip and contemplating her face in front of a mirror, which has been propped against a chair, with her clenched hands raised to her chin. Her braids are tightly bound at the back of her head and she is wondering how she would look if her hair were styled like that of Jane Russell, who stares grimly back from a portrait in the magazine on the girl’s lap. On the floor beside the mirror is a discarded doll; at the girl’s foot is a hairbrush, comb, a lipstick and a tin of rouge, both open. The girl is poised between childhood and womanhood and her innocence hovers in the balance. But though she’ll be prey for the cosmetics industry in a year or two, her wistfulness suggests she already has a sense of proportion about her looks. She won’t be a movie star, but she’ll pass muster. Sometimes children inspire more tenderness when they’re asleep. In Freedom from Fear a painting of a couple tucking in their two young children - the father holding a newspaper that bears a headline containing the words BOMBINGS and HORROR - now seems the most successful of Rockwell’s iconic Four Freedoms, his contribution to the war effort, because it is the least reassuring of the 1943 quartet, which was published in the Post prior to going on tour and being reproduced as posters. Maureen Hart Hennessey has written that “Rockwell’s use of light within the darkened confines of the bedroom…emphasises a sense of warmth and safety”, but the central placement of the newspaper limits the feeling of comfort.

Sometimes children inspire more tenderness when they’re asleep. In Freedom from Fear a painting of a couple tucking in their two young children - the father holding a newspaper that bears a headline containing the words BOMBINGS and HORROR - now seems the most successful of Rockwell’s iconic Four Freedoms, his contribution to the war effort, because it is the least reassuring of the 1943 quartet, which was published in the Post prior to going on tour and being reproduced as posters. Maureen Hart Hennessey has written that “Rockwell’s use of light within the darkened confines of the bedroom…emphasises a sense of warmth and safety”, but the central placement of the newspaper limits the feeling of comfort. As the Fort Lauderdale museum curves to the right, one confronts in the second room of the exhibition the vast expanse of Post covers, only the lowest of which can be scrutinised. These include his portraits of John Kennedy, Nixon, Nehru, and Nasser, technically skilled works of realism that are forgettable alongside the downhome Rockwell. Among the last anecdotal covers was 1960’s Triple Self-Portrait (pictured left; the original painting is also here), Rockwell’s most self-conscious piece. Seen from behind, Rockwell sits at his easel at the moment he is about to start painting a confident Bing Crosby-like portrait he has drawn of himself smoking his pipe, without spectacles. But the face of the painter reflected in the adjacent mirror is that of an uncertain, perhaps anxious man whose eyes cannot be seen behind his glasses. According to the American Chronicles catalogue, Rockwell’s mirror was opposite a large window and his glasses would have reflected the glare of the sun, but the absence of his eyes reinforces the idea that he is not painting what he or we are seeing in reality; the small self-portraits of Dürer, Rembrandt, Picasso and Van Gogh that he has tacked to the top right of his canvas are reminders that painters see with more than their eyes. The painting, which refutes the notion that Rockwell’s paintings can be understood at one quick glance, brilliantly deconstructs the artistic process of composition even as it confounds the notion of realism.

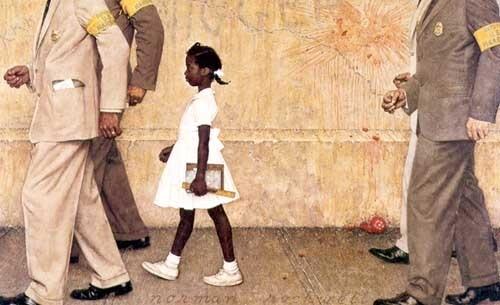

As the Fort Lauderdale museum curves to the right, one confronts in the second room of the exhibition the vast expanse of Post covers, only the lowest of which can be scrutinised. These include his portraits of John Kennedy, Nixon, Nehru, and Nasser, technically skilled works of realism that are forgettable alongside the downhome Rockwell. Among the last anecdotal covers was 1960’s Triple Self-Portrait (pictured left; the original painting is also here), Rockwell’s most self-conscious piece. Seen from behind, Rockwell sits at his easel at the moment he is about to start painting a confident Bing Crosby-like portrait he has drawn of himself smoking his pipe, without spectacles. But the face of the painter reflected in the adjacent mirror is that of an uncertain, perhaps anxious man whose eyes cannot be seen behind his glasses. According to the American Chronicles catalogue, Rockwell’s mirror was opposite a large window and his glasses would have reflected the glare of the sun, but the absence of his eyes reinforces the idea that he is not painting what he or we are seeing in reality; the small self-portraits of Dürer, Rembrandt, Picasso and Van Gogh that he has tacked to the top right of his canvas are reminders that painters see with more than their eyes. The painting, which refutes the notion that Rockwell’s paintings can be understood at one quick glance, brilliantly deconstructs the artistic process of composition even as it confounds the notion of realism.Opposite the array of Post covers is Murder in Mississippi (1965), and a supporting display of notes, photographs and newspaper articles showing how Rockwell came to paint his impression of the nighttime murders of the Civil Rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney by Klansmen in Philadelphia, Mississippi on 21 June, 1964. During his long tenure at the Post, Rockwell had been forbidden from painting black people except in service industry professions. Stirred by the Civil Rights movement and aware his work was overtly WASPish, Rockwell sought to redress the balance once he parted company with the Post in 1963.

Add comment