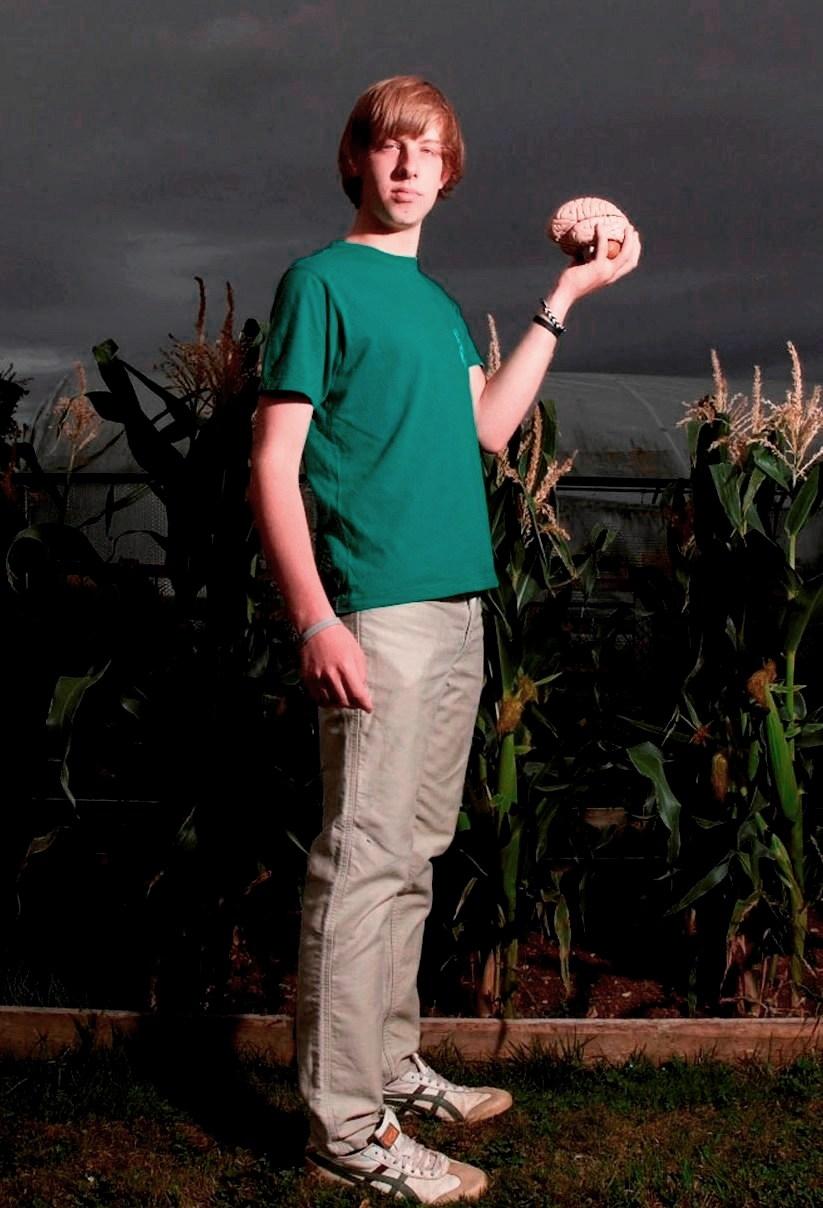

When Simon Hales, a 20-year-old university student, fell from a 20ft wall during a tipsy night out, nobody knew whether he would pull through. He'd suffered a horrific brain injury and would spend the next five weeks in a coma. Luckily, he did pull through, though nobody could recognise the newly awakened Simon from the old Simon. His mother told us that her son "evidently wasn’t Simon”. She loved him, she said, but “what I'm looking for is the son that I had to come back".

Simon emerged from his coma in what seemed at first to be a blissfully unaware state. He could remember nothing of his life before the accident, and he could not remember the accident itself, although he asked about it obsessively. He had also lost his short-term memory. One shopping trip, taken with his care worker, appeared to prove the insurmountability of the most basic task. But this in itself did not appear to unduly phase him, since every event was passed through in a fug of consciousness. It was only in the months ahead, when some self-awareness began to develop, that he became angry and frustrated, developing a particular hatred for the family pet lurcher, Spider, whose particular crimes the viewer remained oblivious to.

“I think of this as a prison,” he said of Oakleaf, the rehabilitation unit for brain-injured men that was currently his home. “And I don’t know why I’m here. I’ve done nothing wrong.” But he was, in fact, becoming all too aware of why he was there, and there was an especially poignant part of the film that took Simon and his mother back to where the accident had taken place. It was at that point that Simon appeared to understand that the old Simon was never coming back.

Zac Beattie’s Cutting Edge documentary followed Simon’s progress over six months. His mother and three brothers tell us about the kind of lovable perfectionist Simon was before the accident - dripping dishes would drive him mad, and he had this funny way of dancing by spinning in one spot. One of his younger brothers tenderly tucks Simon into bed, while another teaches him how to hold his toothbrush properly. They too know the old Simon will never return, so they are learning to renegotiate their relationship with him.

Although this was a film about the progress of one young man following a severe brain injury, it also raised questions about the nature of personal identity. “You can’t blame everything on your brain injury,” his mother tells him, when his frustrations were once again getting the better of him. He had perhaps found a ready excuse for his explosions of temper, but it seemed that the “prison” that Simon had longed to escape was not just represented by the walls of the rehab unit.

But this sad, tender film was far from depressing. Simon had the love of his close-knit family, and there was hope for much improvement yet. We could also see just how much dedicated care he was receiving at his specialist unit, as just one of 135,000 people sustaining a head injury in Britain every year.

Simon emerged from his coma in what seemed at first to be a blissfully unaware state. He could remember nothing of his life before the accident, and he could not remember the accident itself, although he asked about it obsessively. He had also lost his short-term memory. One shopping trip, taken with his care worker, appeared to prove the insurmountability of the most basic task. But this in itself did not appear to unduly phase him, since every event was passed through in a fug of consciousness. It was only in the months ahead, when some self-awareness began to develop, that he became angry and frustrated, developing a particular hatred for the family pet lurcher, Spider, whose particular crimes the viewer remained oblivious to.

“I think of this as a prison,” he said of Oakleaf, the rehabilitation unit for brain-injured men that was currently his home. “And I don’t know why I’m here. I’ve done nothing wrong.” But he was, in fact, becoming all too aware of why he was there, and there was an especially poignant part of the film that took Simon and his mother back to where the accident had taken place. It was at that point that Simon appeared to understand that the old Simon was never coming back.

Zac Beattie’s Cutting Edge documentary followed Simon’s progress over six months. His mother and three brothers tell us about the kind of lovable perfectionist Simon was before the accident - dripping dishes would drive him mad, and he had this funny way of dancing by spinning in one spot. One of his younger brothers tenderly tucks Simon into bed, while another teaches him how to hold his toothbrush properly. They too know the old Simon will never return, so they are learning to renegotiate their relationship with him.

Although this was a film about the progress of one young man following a severe brain injury, it also raised questions about the nature of personal identity. “You can’t blame everything on your brain injury,” his mother tells him, when his frustrations were once again getting the better of him. He had perhaps found a ready excuse for his explosions of temper, but it seemed that the “prison” that Simon had longed to escape was not just represented by the walls of the rehab unit.

But this sad, tender film was far from depressing. Simon had the love of his close-knit family, and there was hope for much improvement yet. We could also see just how much dedicated care he was receiving at his specialist unit, as just one of 135,000 people sustaining a head injury in Britain every year.

- Watch My New Brain on Channel 4od

Comments

Add comment