World War One poems can become too familiar. So can the war itself, its five years of centenary commemorations so far suffering from excessive patriotism, a sense of uncomprehending disconnection from the gone generation which lived it, and a politically expedient veil drawn over its holocaust, the Armenian genocide. The Lads In Their Hundreds combines contemporary English music and French war poetry unknown here to more intimately recall the time’s voices. As the poems’ performer, Tcheky Karyo, mentions in an after-show talk, some of them were written huddled over trench candlelight. They insist on private realities in a general catastrophe.

This Brighton Festival performance was the only UK chance to see a Comedie de Picardie production otherwise restricted to France. English tenor Edmund Hastings swaps his blue French uniform in those earlier shows for British khaki, more appropriate for music largely by trench veterans Vaughan Williams and Ivor Gurney. Williams’ settings of AE Houseman’s A Shropshire Lad poems (which give The Lads In Their Hundreds its title) and Gurney’s nostalgia for Gloucestershire’s majestic green hills fix an ideal England as a distant beacon. Though some of the music has folk roots, the bawdy, knowing music hall hits of Oh What A Lovely War are replaced by a more restrained sadness. These are the art-songs of the war’s middle-class victims, their sense of tragedy decently buried, their yearning for home a poignant contrast to the carnage around them.

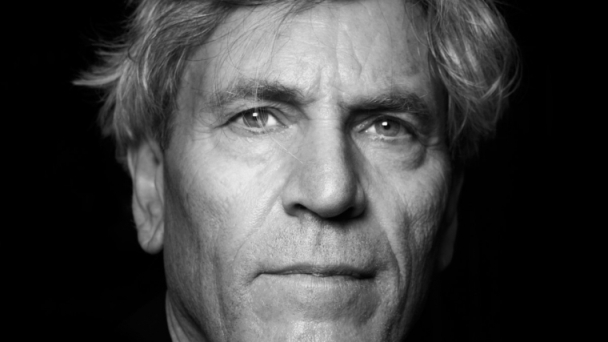

Hastings’ lone Englishman is first glimpsed, ghost-like, behind a backdrop of a darkening trench landscape. He embodies the music’s quiet nobility, suggestive of English parlours as much as hills. Pianist Edward Liddall and violinist Michael Foyle are his accompanists in Jean-Luc Revol’s spare production, in which Karyo alone, pictured right, represents the French soul at war. Most familiar in Britain for The Missing, he has been a potent star for decades. His animated style here, throwing his whole body into poems by Apollinaire, Cocteau and others, lessens dependence on the translation booklets. For Maurice Gauchez’s “Les gaz”, he grabs his face and violently rages as the words’ mustard gas hits, before the violin’s climbing hope and shivering fade in Vaughan Williams’ A Lark Ascending.

Hastings’ lone Englishman is first glimpsed, ghost-like, behind a backdrop of a darkening trench landscape. He embodies the music’s quiet nobility, suggestive of English parlours as much as hills. Pianist Edward Liddall and violinist Michael Foyle are his accompanists in Jean-Luc Revol’s spare production, in which Karyo alone, pictured right, represents the French soul at war. Most familiar in Britain for The Missing, he has been a potent star for decades. His animated style here, throwing his whole body into poems by Apollinaire, Cocteau and others, lessens dependence on the translation booklets. For Maurice Gauchez’s “Les gaz”, he grabs his face and violently rages as the words’ mustard gas hits, before the violin’s climbing hope and shivering fade in Vaughan Williams’ A Lark Ascending.

A hip-glass appears for A Fourtier’s “A la gnole” (“To hooch”) as Karyo squats, swaying and toasting. In the talk afterwards, he mentions a “duty of memory”, and he is animated by rage and pity. The latter emotion enfolds Georges Duhamel’s “Ballade de Florentin Prunier”, in which a mother’s 20-day vigil by her wounded son ends with him dying as soon as she sleeps, “silently, so as not to wake her”.

Occasional, shocking artillery bursts and suggestions of searchlights stud what is in essence a recital and reading. Apollinaire’s faintly surreal reaction to the trench life he abandoned bohemian Paris for is among the specifically French touches. A human ache for the beauty of summer landscapes, soft breasts, boozy oblivion and the art which describes them, individually defying industrial slaughter, is what lingers from this thoughtful, finely weighted production.

Comments

Add comment