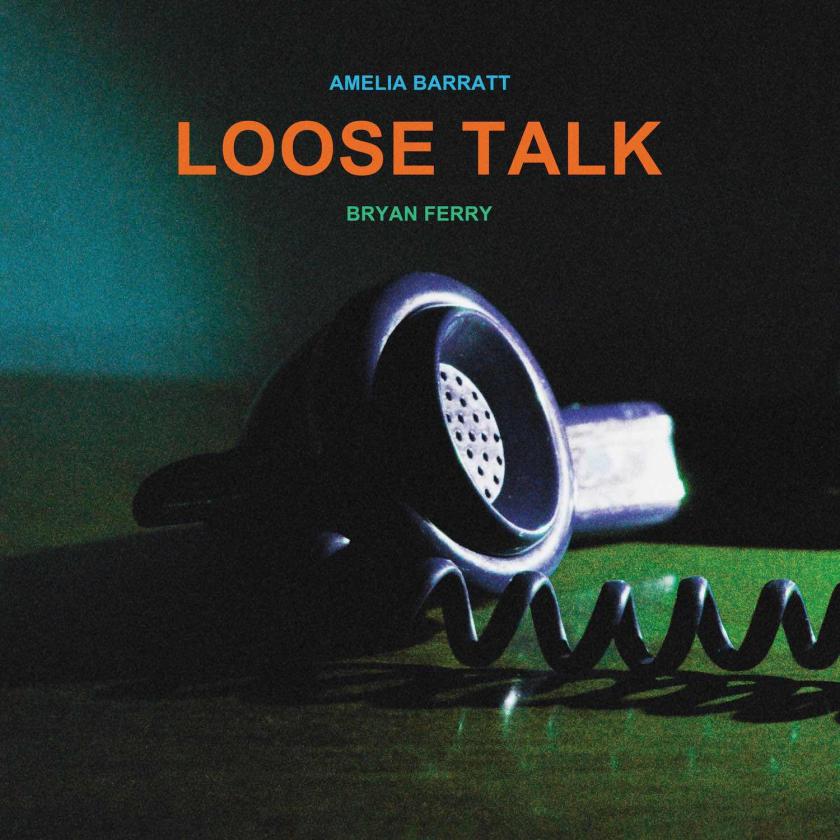

On the spoken word LP Loose Talk, Amelia Barratt reflects on her or other women’s experiences, real or imagined, over tunes drawn from Bryan Ferry’s demos, some from early in his career. To hear his instantly recognisable sound applied to a female sensibility, especially that expressed with such confiding intimacy by the painter, writer, and performance artist Barratt, makes for a unique and satisfyingly unsettling listen.

Barratt enunciates her miniaturist monologues understatedly but not insouciantly. If her white, middle-class English diction seldom betrays emotion, her observations on people, objects, and fragments of conversation are charged with feeling, ruefulness not least.

Her imagery is precise – “A lit match catches one drop of orange oil/ from a piece of peel” – but the scenarios she describes are opaque, like short stories without endings. All carry metaphorical weight, the narrator’s momentary impressions capturing the current state of her or a character’s life.

In Roxy Music, Ferry would sometimes slow his croon to address lovers at near-talking pace – the flesh and blood sirens of “Chance Meeting”, “Mother of Pearl”, and “Bitter-Suite”, the plastic one of “Every Dream Home a Heartache”. He must have intuitively matched his jinking, jazz-tinged melodies to Barratt’s blank verse.

His unhurried piano-playing introduces most of Barratt’s poems, then anchors the melodies as they meander behind or underneath her voice; among the musicians Ferry enlisted to help enhance the demos, Roxy’s drummer Paul Thompson quietly and stealthily keeps the beat,

The album’s first two pieces are woman-on-the-town nocturnes, which resonate with the melancholy strain in the more jaded of Ferry's nightlife songs. In “Big Things”, the protagonist is a teacher nervously waiting at a hotel bar for her date to show. “Stand Near Me” tells of another waiting woman – seemingly a competitive dancer past her best – who restlessly flips TV channels in a hotel room.

I could have done with more of this big city vibe, redolent as it is of Edward Hopper’s urban paintings, but Barratt only offers further glimpses of it in the last two pieces, “White Noise” and the relatively fast title track.

In the intervening poems, one of Barratt’s narrators spies on a flower seller working in his stall, who (if I’ve interpreted this correctly) turns out to be the partner she is unhappily resigned to living with (“Florist’); another visits an elderly seamstress (“Cowboy Hat”). There are visits to a concert (“Orchestra”), to a funfair ("Landscape”), and to the seaside with a child (“Holiday”); these last two afford rare summery workouts for Bryan Ferry tunes. It's comforting to hear him distantly vocalising on "Orchestra".

Barratt includes autobiographical elements. “What is the difference between ash/ and snow/ She asked me in the interview,” says Barratt the painter, uprooted to the country in “Pictures on a Wall.” The teacher recurs in “White Noise”. The blurring of the lines between personal confession and anecdotal portraiture keeps us guessing, while Ferry’s languid rhythms compound the record’s suggestion that everyday living is mysterious.

Add comment