First Light, BBC Two

Born in Stockport in 1959, Tibor Fischer is the son of two Hungarian basketball players who fled their homeland during the 1956 revolution; his 1992 Booker-nominated debut novel, Under the Frog, revisited this subject in wonderfully fleshy, blackly comic form. In 1993 Fischer was included in Granta's influential list of the 20 best young British writers, and in the ensuing two decades he has fulfilled that promise with a series of richly rewarding novels and short stories.

By complete coincidence, this afternoon I tuned in to Air Force, Howard Hawks's 1943 propaganda picture: chiselled young airmen fill a B-17 "flying fortress", dropping their payloads over Japan, both a news service and wish fulfilment for domestic audiences. Their sharp, sweaty features glow in the firelight. Their commanders are tough but fair. Their bombs fall crisply, in a noble cause. This is not that film.

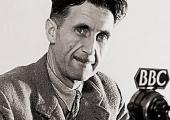

Every great novel is a world, and every great novelist responds to and recreates their own time in their own image. Therefore how could a three-part documentary series possibly cover that fertile period in British literature that took in both world wars and their aftermath? Of course it’s an impossible task but it’s one that is neatly circumvented here because these programs are really just an excuse for the BBC to dust off some old tapes of some of our greatest writers speaking about their work.

The Yesterday channel’s ongoing “Spirit of 1940” season has provoked a giant surge in its viewing figures, another reminder of the grip World War Two still exerts on large chunks of the British public. The Battle of Britain in particular has become a self-contained historical moment emblematic of what the British regard, or at least used to regard, as their finest characteristics – patience, courage, stoicism and a dogged refusal to accept bullying European dictatorships. Maybe we haven’t quite let go of that last part. Perhaps the story of our Boys in Blue in the late summer of 1940 gains additional resonance from the way it contrasts so starkly with the meandering aimlessness of Britain’s recent military adventures. It was a battle with a purpose, won by the Brits without any help from the Americans.

The part played by Polish fighter pilots during the Battle of Britain has hardly gone undocumented, and the Hun-zapping exploits of the Polish 303 Squadron will be familiar to anyone with a historical interest in the subject, so you’d have to say that calling this film The Untold Battle of Britain was a wee bit of an exaggeration.

This 1969 Italian movie has accrued a somewhat baffling mystique, not least because of the way it has been lavished with praise by the excitable Quentin Tarantino. This DVD issue includes a hilariously amateurish short of Tarantino hosting a low-rent showing of the film in Los Angeles, followed by an onstage chat with director Enzo G Castellari, clearly amazed to have been invited. He doesn't have to say much, since Tarantino just keeps babbling non-stop about how great he is.