Waldemar Januszczak always has a provoking agenda to shape his now nearly countless forays into television art history. In this four-part series he's out to challenge what he sees as the unthinking acceptance of the one-dimensional traditional and monopolistic version of the Renaissance.

He assumed we all blindly agreed with that second-rate painter but potent myth-maker Vasari (born in Arezzo, lived in Florence), who, in his 1550 biographical three-volume Lives of the Artists, set out the case for the innovative supremacy of contemporary Italian art – the Renaissance. Vasari indeed was the first to use "Renaissance" in this context. He suggested in a series of over-the-top essays that the painters, sculptors and architects of Italy, and specifically Florence, made a crucial break with medieval templates to forge a new humanistic art.

Vasari’s Lives is conventionally thought of as the first book of art history, not to mention the most influential art book ever written. He paid hardly any attention to the contemporary art of the North except to that arrogant genius of Nuremberg, inventor of the self-portrait, Albrecht Dürer – although Januszczak didn’t mention that Dürer visited Italy. The new art was based on the rediscovery of the arts of antiquity, that perfection reached by the Greeks and Romans (Dürer self-portrait, right).

Vasari’s Lives is conventionally thought of as the first book of art history, not to mention the most influential art book ever written. He paid hardly any attention to the contemporary art of the North except to that arrogant genius of Nuremberg, inventor of the self-portrait, Albrecht Dürer – although Januszczak didn’t mention that Dürer visited Italy. The new art was based on the rediscovery of the arts of antiquity, that perfection reached by the Greeks and Romans (Dürer self-portrait, right).

Most prominent was Vasari’s hero, Michelangelo, as image-making in the west was revolutionised. Vasari referred to the art of the north as gothic, indeed even barbaric. According to Januszczak, this view has prevailed over five centuries of subsequent art and art history. The jingoistic Florentine Vasari presented a rousing tale of cultural triumph in what our impassioned narrator called the great football match of civilisation: Florence 1, Rest of the World 0.

Oh no, insisted Januszczak, who left sunlit Italy to stomp about from Brussels to Bruges, and Stockholm to Nuremberg: Januszcak, both writer and presenter, obviously saw himself as an original myth buster. It all happened really elsewhere, not under blue Italian skies but up north. The Northern Renaissance invented oil paint, when those pesky Italians just did frescoes; and they also invented the depiction of genuine human emotion, expressed with the utmost skill in idioms of potent realism. Not for Rogier van der Weyden the enigma of the Mona Lisa, but real translucent tears for the Virgin at the death of her Son.

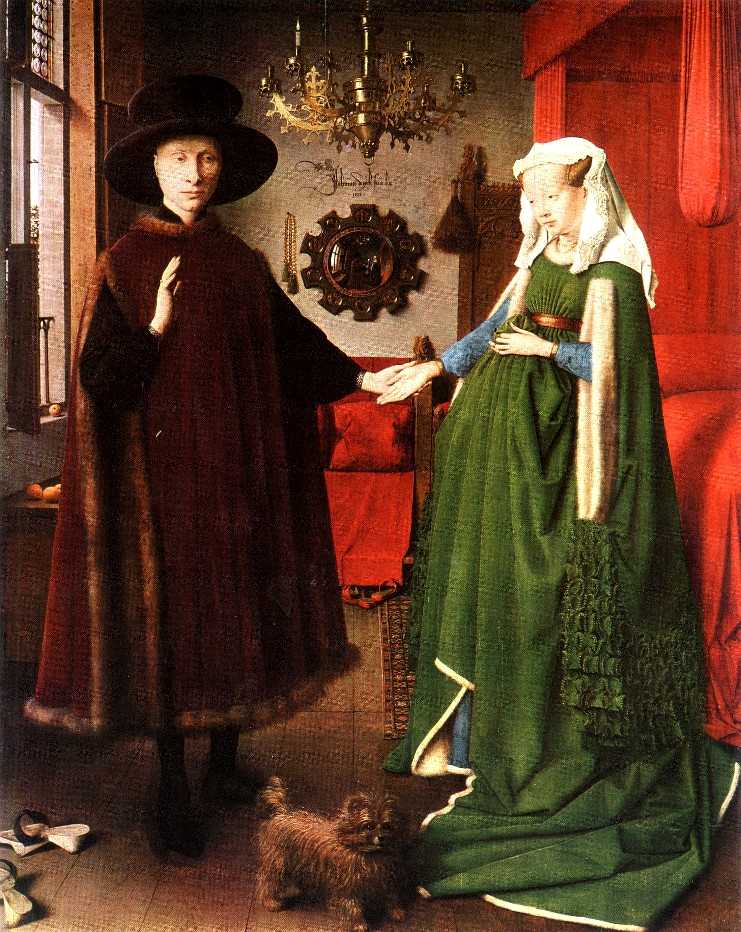

In the opening sequences our guide was lugging a battered suitcase which was finally unpacked in Bruges, where Januszczak unfurled quantities of material, like that which clothed the couple in Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (pictured left). Startling facts emerged: Giovanni Arnolfini was a wool merchant from Lucca who spent most of his life in Bruges, the wealthy trading city of Flanders. His costume was adorned with the exceptionally expensive pelts of pine martens, perhaps 200 of them; but we were told that the bulk of his companion Giovanna’s green dress, so often thought to show that she was pregnant (the couple actually never had children), was because its lining was made from the white chest fur of red squirrels, minever, 2000 of them. It was unimaginable luxury.

In the opening sequences our guide was lugging a battered suitcase which was finally unpacked in Bruges, where Januszczak unfurled quantities of material, like that which clothed the couple in Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (pictured left). Startling facts emerged: Giovanni Arnolfini was a wool merchant from Lucca who spent most of his life in Bruges, the wealthy trading city of Flanders. His costume was adorned with the exceptionally expensive pelts of pine martens, perhaps 200 of them; but we were told that the bulk of his companion Giovanna’s green dress, so often thought to show that she was pregnant (the couple actually never had children), was because its lining was made from the white chest fur of red squirrels, minever, 2000 of them. It was unimaginable luxury.

Meanwhile the lifesize carving of the Bamberg horseman of 1220 was contrasted, favourably, with Donatello’s equestrian statue in Padua, The Monument of Gattemelata, from 1450, more than two centuries later: the North wins again. Januszczak attributed the superb achievements of the German and Flemish territories to the invention of oil paint (although according to him it was actually invented in 700 AD or so in Afghanistan, for Buddhist paintings), optics, lenses and spectacles, the better to aid the artist’s vision. Hyperbole held no terrors for Januszczak: Flemish artists produced an “art that can paint miracles”.

It was an enormous pleasure to see a number of great paintings, but why presenters have to present in front of them is an insoluble mystery of most art programmes - Waldemar! Out of the way! And as usual we had unnecessary uplifting music to whip up excitement. The lack of helpful subtitles to give us names and locations so that we might possibly some day see for ourselves was another irritant. A quick mumble from the narrator will not suffice.

Comments

Add comment